Home/Journal/Uncategorized /

The Anatomy Of A Fishing Hook

SKU: ET-ART2-TAOAFH

Published on: 24 Aug 2016

The humble fishing hook, has been around for quite a while. In fact, since Biblical times and that is a long time.

Fast forward to today, and little has changed with its purpose - that is, to catch fish.

Regardless of application, what remains common is its anatomy.... read more.

Published on: 24 Aug 2016

Last update: 27 Aug 2016

Author: Andrew Luke Tan

The humble fishing hook, has been around for quite a while. In fact, since Biblical times and that is a long time. Reference to such a device was first made in the Book of Job (verse 41:1) that was thought to have been written around 2000-1800 B.C.

Fast forward to today, and little has changed with its purpose - that is, to catch fish. Made first from stone, then bone, the modern fishing hook is now made of steel to suit specific applications.

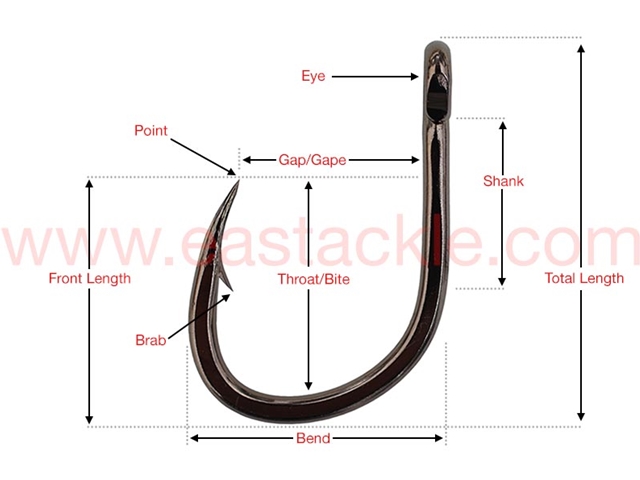

Regardless of application, what remains common is its anatomy, the parts of which are described below.

Point - This is the business end of the hook, the first part to connect with the fish, that probably makes it regret taking your lure/bait. Sharpness is key. A blunt hook will not likely catch you fish. Hook points can be sharpened, though some will retain their sharpness better than others, depending on the material it is made of. Different types of hook points have been created - round point, knife edge, cutting point etc, all designed for a different purpose or application.

.jpg)

Barb - This is the reverse point designed to keep fish from coming off the hook. Barbs can be inward or outward facing. Size and angle of the barb does matter. The bigger the the barb and the wider its angle, the hard it is to set the hook. However, if it can be set, that fish ain't going to be let off the hook too easily, particularly if it is bony jawed. But the down side with size and angle is the damage that a pronounced barb can do to softer jawed fish and to soft tissue. Many catch and release anglers will use barbless hooks or debarbed hooks to minimise injury and promote sustainability. And besides, it is alot easier and less painful to remove a debarbed / barbless hook from yourself if you do get hooked. A barbed hook can be easily debarbed by crimping down on the barb with a pair of pliers, which will either flatten or break the barb off, particularly with high carbon / hardened steel hooks.

Bend - This is the curved section of the hook, that probably sees the most amount of variation in construction, shape and design for different purpose or application. If anything, the construction of this section, more often than not, for right or wrong reason, makes or breaks the reputation of any hook. The bend plays a major role in determining the strength of the hook, in terms of how easily the hook tip will open when the fish decides to take off with it in its mouth (or if foul hooked). Strength is dictated, amongst other things, by the size of the wire gauge, the carbon content of the wire, the hardness of the metal, the shape of the bend, the gap size of the hook, and the depth of the hook's throat. Hook manufacturers balance each of these considerations when designing a hook to meet a particular application.

Throat/Bite - Otherwise, known as the bite for the fish to chomp on, this is the section of the hook, measured from height of tip point, to the lowest point in the bend. The deeper the throat, the more hook there is to potentially penetrate into the fish. However, more does not always mean better. The deeper the throat, the greater the leverage the fish has to put pressure on the lower section of the hook point to open its gap, and the higher the chance, of losing your fish.

Shank - This is the backbone of the hook, the section measured from the top of the bend, to the bottom of the eye of the hook. The application of the hook, more often than not dictates the length of a hook's shank. Bait hooks with a longer shank will allow for more bait to be strung onto the hook. Luring hooks with a longer shank will expose more of the hook from the body of the lure to increase the chances of a hook up. However, a longer shank means increased leverage for it to be bent or the likely potential to affect the swimming action or buoyancy of the lure because of its added weight (particularly when it comes to treble hooks).

Gap/Gape - This is the width of the hook measured from tip to hook shank. The wider the gap, the higher the potential to set a hook into a fish, as more of its point is exposed for action. However, the down side is that it weakens the strength of the bend as the fish has more leverage to open the hook tip when it decides to put the pedal to the metal and make a run for it.

Total Length - This is the section of the hook measured from the top of the eye to the bottom of the bend.

Front Length - This is the section of the hook measured from tip of the hook to the bottom of the bend.

Eye - Most single hook eyes run perpendicular to the bend of the hook. Depending on the application of the hook, the eye could be turned up, turned down or straight. However, the eyes of single luring hooks are in line and run in the same direction as the hook's bend. Most eyes are opened / ring-eyed, whilst some are closed, i.e. the hook eye has been brazed closed to add strength to prevent the eye from opening under strain. Some hooks do not have an eye, but a spade / flattened end.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Wire Gauge - This refers to the diameter / thickness of the wire that is being used to make the hook. A lighter wire, will likely bend or break with greater easier under pressure, but a heavier wire, although stronger, means more weight, and the increased potential to affect the swimming action or buoyancy of the lure. Particularly for treble hooks, certain manufacturers will classify the wire gauge being use by an X-rating e.g. 2x, 3x, 4x, to detonate the increasing thickness and strength of the wire. However, there does not currently appear to be any standard set between hook manufacturers to objectively measure the strength of each rating increase. Until such time, such ratings perhaps are best used as a means of differentiate between different models (of differing ratings) from the same manufacturer rather than comparing hooks from different manufacturers.

Hook Material - Hooks are mainly made of stainless steel or high carbon steel. Stainless steel is selected for its rust resistance and great for saltwater use. However, they are not as strong as high carbon steel and usually heavier in comparison to an equivalent high carbon steel hook, as a heavier wire gauge is required to attain an equivalent strength. However, it is thought that stainless steel is less eco-friendly to fish (in comparison to a high carbon steel), as it takes much longer for it to corrode away, and in turn, increases the risk to the health of the fish if the hook restricts its from feeding or its mobility. Hooks made of high carbon steel are not only just lighter, but stronger in comparison to an equivalent gauged stainless steel hook. However, carbon steel hooks are prone to rusting and require a surface finish to create a barrier layer to inhibit corrosion.

Carbon Content of the Hook - The higher the carbon content, the harder the hook, the better the retention of hook sharpness, but the higher the chance of it snapping under stress instead of bending and deforming out of shape. To prevent this from occurring, high carbon steel hooks are tempered, to increase its strength by decreasing its brittleness through the process of tempering.

Tempering - This is the process of heating metal to an optimum temperature and allow it to cool in still air or in an oil bath to increase the strength of the hook but decreasing its brittleness.

Finish - This is the process of coating of the hook with a surface layer that acts as an inhibitor to rust. Common barrier layers include black nickel, tin and gold plating. In more recent times, titanium and PTFE (aka Teflon) are being used as a finish on hooks to prevent rusting.